Gold and silver lace of the 17th - early 20th century

Gold and silver lace first appeared in Russia in the second half of the 16th century. This kind of applied and decorative art came from Western Europe. Throughout the 17th and the first half of the 18th century lace was brought to Russia in numerous finished products and in abundance of high quality gold and silver threads, which were used in embroidery and lace-making. Love for gold and silver lace, and its prevalence, especially in the 17th century Russia, was primarily due to its decorativeness that was in perfect harmony with large-patterned heavy fabrics, with loose-fitting clothes and with magnificent pearl and golden thread embroidery that reached a peak in the 17th century. Gold and silver lace was used for reach decoration of the tsar, boyar and princely clothes, noble dresses and church vestments, various everyday secular and church objects. In the 18th century, it penetrated actively into folk life.

The Inventories of the Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery of the 17th – early 20th century prove that gold and silver lace was widely used in church life. Thus, the earliest surviving Inventory of 1641 enumerates 15 works with lace, including the sacristy items: “four palls of red smooth velvet with crosses embroidered in a single thread of Kaffa pearls, outlined with bullion. The edges are trimmed with golden lace. Donation of Tsar and Grand Prince Boris Feodorovich of all Russia”. The Inventory of 1735 records about 30 items with lace, and the Inventory of 1756 mentions over 50.

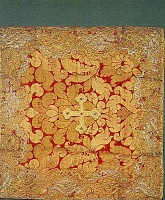

The centers of lace-making could be boyar and princely workshops, as well as nunneries, where talented needlewomen worked. The earliest specimens of gold and silver lace in the Museum collection date back to the second half of the 17th century. The favorite motifs in the 17th century gold and silver lace were carnation and tulip, typical of all Russian and West-European ornamental art at that time. These motifs were most characteristic of Flemish lace. The samples of lace with carnation and tulip patterns present one of the main groups of ornaments in the Museum collection.

In the 18th century, when European dress spread, lace gradually disappeared from noble life, and in the second half of the 18th century it was completely replaced by lace of thing thread that was very fashionable in Europe. Yet, at the same time, gold and silver lace was widely used in church objects. In the 18th century, they used the carnation and tulip motifs, as, for example, in the phelonion of crimson brocade with large silvery pattern. At the beginning of the 18th century, various compositions of Russian agramant developed. The floral and geometrical ornaments were most characteristic of agramant in the first half of the 18th

century. Such ornamental elements as “curved tape”, festoons, “filet”, fan-shaped motifs further developed in the 18th – 19th century thread lace

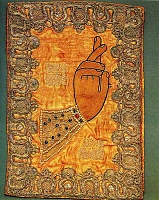

The floral and geometric ornaments of the second half of the 18th century are complicated, but strictly rhythmic and clearly composed. In the mid-18th century, lace was supplemented with flattened and colored (blue, red, green) wire, which greatly increased its decorative effect.This technique was characteristic only of Russian metal lace-making illustrating its tendency for illumination. There appeared the so-called filet lace. One of the specimens is the vexillum of silver and golden filet with Metropolitan Platon’s monogram. The vexillum is trimmed with silvery fringe.

The 18th century lace of West-European origin, called “point d’Espagne” in Russia, presents a special group in the Museum collection. It was very expensive. So only privileged society, where it was very popular, could afford it. “Point d’Espagne” is guipure of very thing golden and silver braid, or spun thread in coupling technique. As a rule, it was used in female dresses and hats, and in male camisoles.

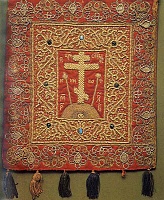

The Museum exhibits with “Point d’Espagne” are entirely church articles. It decorates the icon-cloth of red satin with the pearl Golgotha cross and ornamental boarder, donated to the Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery in 1638 in memory of the clerk in the Boyars' Council I.T. Gramotin. Lace, probably attached in the first quarter of the 18th century, did not destroy the compositional integrity of the icon-cloth. Braid lace frames the purificator of pink satin, originated in Europe

The chasubles and surplices with French “Point d’Espagne” were preserved in the archimandrite sacristy of the Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery in the mid-18th

century. There was also kept the surviving brocade epigonation, decorated with the same type of lace with patterns of thin fibrous stems with outgoing tetrapetalous flowers..

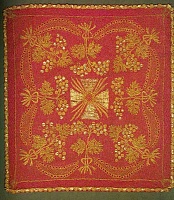

In the 18th century, gold and silver lace penetrated into folk life. There are two works of folk art with golden lace of the late 18th – early 19th century. In 1842, general Glazov’s wife donated to the Trinity-St.Sergius Monastery an aer and two purificators of golden filet lined with lilac silk. The items of filet are mainly referred to the 19th century, among them the complete sets of church objects are not rare.

In the 19th century, multi-colored chenille embroidery in cross and satin stitches was very popular. These techniques were often combined with gold and silver filet. Mother Superior Maria Tuchkova of the Savior Nunnery in Borodino Field donated to the Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery an aer and two purificators of golden filet with large quadrangular holes. They are decorated with a floral pattern embroidered in bright red, green and blue chenille

In the 18th – 19th century, white silk-lace (blond-lace) was very popular in West Europe and in Russia. Its main peculiarity was a contrast between a very thing tulle background and massive ornament. Interlaced golden and silver thread made it exceptionally refined. Two samples in the Museum collection could presumably date back to the mid-19th century. One of them is the edge of the velvet phelonion of the early 20th

century, originating from the Optina Pustyn.

We should also consider gold and silver lace-making in the 19th – early 20th

century, i. e. in the last period in the development of this art. It was used only in church and peasant life. In the 19th - early 20th century, metal lace was traditionally made in nunneries.

The icon-cloth and purificator of grey silk with a pattern of roses and silver lace, donated by the Khotkovo Mother Superior Sergia, date back to the late 19th – early 20th century. The icon-cloth and purificator of silvery glacet with multi-colored silk embroidery and narrow golden edge with festoons passed to the Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery in 1903.